It’s a distressing sensation – struggling to find once familiar words, stumbling over simple sentences that used to flow easily. For those separated from their native linguistic environment for years, losing grip on a childhood language can be an unnerving experience. Even for the elderly, skills in a first language learned decades ago can mysteriously erode over time. What causes our mother tongue to slip away without regular use?

Pathways Forged Through Early Immersion

Scientists point to how intricately language becomes wired within the architecture of our brains starting from infancy. Neural pathways devoted to both comprehending and formulating speech are forged through daily linguistic engagement. Vocabulary, grammar rules, and even accents imprint through immersive exposure and practical needs during our formative years.

However, neuroplasticity allows our brains to continually reshape connections in response to life experiences. As we enter new cultures with different majority languages, the neural real estate once occupied by our native tongue gets gradually repurposed if left inactive. The links between memory, meaning, and vocabulary words dim without rehearsal. The pathways rust over time, just as an unused walking trail slowly becomes overgrown by vegetation.

Adult Brains Still Plastic

Even as adults, if we cease using a language for work, family, and social life, it can surprisingly destabilize our mental framework. Brain scans of those who learned a second language at 10 years old or younger show more overlapping activation between both languages – suggesting deeper, more unconscious processing centers get engaged. This may strengthen retention later in life. In contrast, languages learned later rely on more easily disrupted explicit memory pathways.

Hope Yet for Reawakening

However, all is not lost for those seeking to revive childhood fluency. Through conscious re-study, especially of commonly used vocabulary suited for daily life, some reconnect and reactivate their old neural links. Immersed conversation with native speakers also helps reshape language areas of the brain.

In one remarkable case, a man who had not spoken Polish – his forgotten childhood language – for over 70 years spent 6 months in intense immersion at age 89. Incredibly, PET scans confirmed his brain had begun processing Polish in the same region that handles his dominant English, indicating a “mother tongue” imprint so potent it may never disappear entirely from our neural architecture.

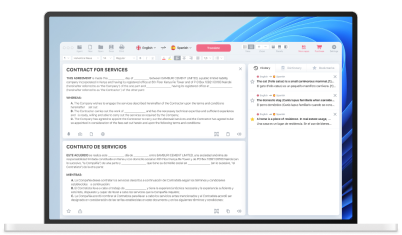

Such examples have prompted suggestions for how governments could better support heritage language retention for diaspora communities. Apps modeled on commercial platforms, but focused on endangered native languages could aid descendants seeking to bolster fading family tongues. Cultural centers hosting traditional dance, food, and art can also unite far-flung groups. Translating oral histories to text via services like the Lingvanex translator provides searchable records if firsthand speakers eventually pass on.

Perhaps most profoundly, master linguists believe the ghostly presence of our mother language always remains imprinted within our brains’ pathways, however faintly. Like a mysterious code our mind still unconsciously recognizes, those early language patterns permeate how we think and process meaning our entire lives, influencing future languages we learn. Services to translate English to Urdu may help South Asian diasporas retain their heritage language.